Drawing the Line Between Troubleshooting an Amp and Modifying It

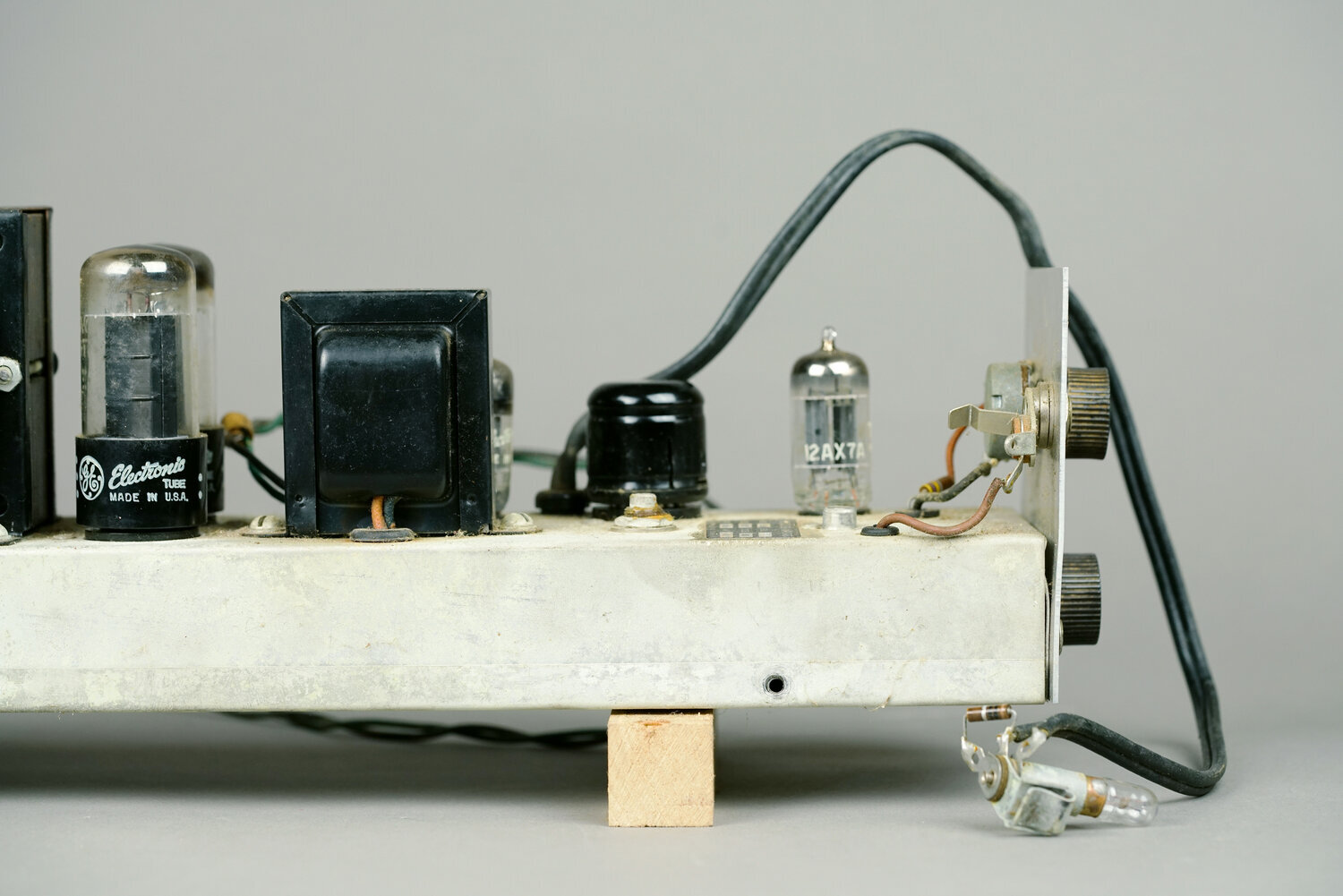

Detail from a Wurlitzer 700 amplifier.

When you repair an amplifier, you have two choices. You can bring it back to its original state by fixing only what is broken. Or, you can improve the circuit by modding it.

There is a lot to love about an amplifier that is in fully-functioning, but original, condition. When using a vintage amp, you are playing music on a slice of time. You are combining two different musical periods in a way that is impossible to replicate with any other gear. It’s basically time travel.

Your music is influenced by everything that happened in previous decades. But the amp was finalized forty or fifty or sixty years ago. It is an evolutionary mile-marker. It can’t change (of course: it’s inanimate), but it embodies the moment that it was made. When you play it, you are returning to the point of its creation, when some circuit designer or executive or musical consultant of some kind decided that this sound was the sound: the sound that the kids were going to like, the sound that the bands were going to like, the sound that might end up on the records and the radio. The sound that would make people want to buy this amp. Even if the amp was low-budget and derivative, somebody believed that its sound was an adequate facsimile of the sound.

So, when you play the amp, you are bringing all your influences and all of your ideas to this piece of gear. And the piece of gear, in return, is giving you a certain sound that is the product of the year that it was created. In using these old sounds to make new music, its almost like rewriting history.

A vintage Dynavox widowmaker amplifier, which we modified (in part to add a power transformer).

But, like any union of now and then, you and your amplifier are working across a generation gap. Your use of the amplifier is likely something that its designers could not have predicted. Micing the amp into a mobile interface and recording into a laptop can be done today with a few minutes and a few hundred dollars, but it would have been science fiction in the 1950s. And, on the flip side, the amplifier is probably not 100% meeting your standards either. Recording in the 1950s meant arranging the entire band around one microphone and performing the song in a single take. Nobody needed an aux output, and somehow everyone seemed to accept the fact that sometimes your electronics might shock you a little bit now and again.

And there’s another fact: everything ages. Metal rusts. Paper disintegrates. Capacitors leak. Things just break. Most of these things can be replaced! But some components are more opaque than others. In many cases, it can be difficult to spec an adequate replacement, because some things just aren’t made anymore. Even if you do find an equivalent part, does it fit in the same mounting holes? Does it perform just like the original? Or is it different in subtle, tone-changing ways? Should you even replace the part at all, or should you mod the circuit to work around it?

So: there is definitely something magical about using an original vintage amplifier. At the same time, it’s extremely impractical. Most mods help balance that by bringing the amplifier into a state that is easier to record, more convenient to perform with, and suits the player’s musical style better.

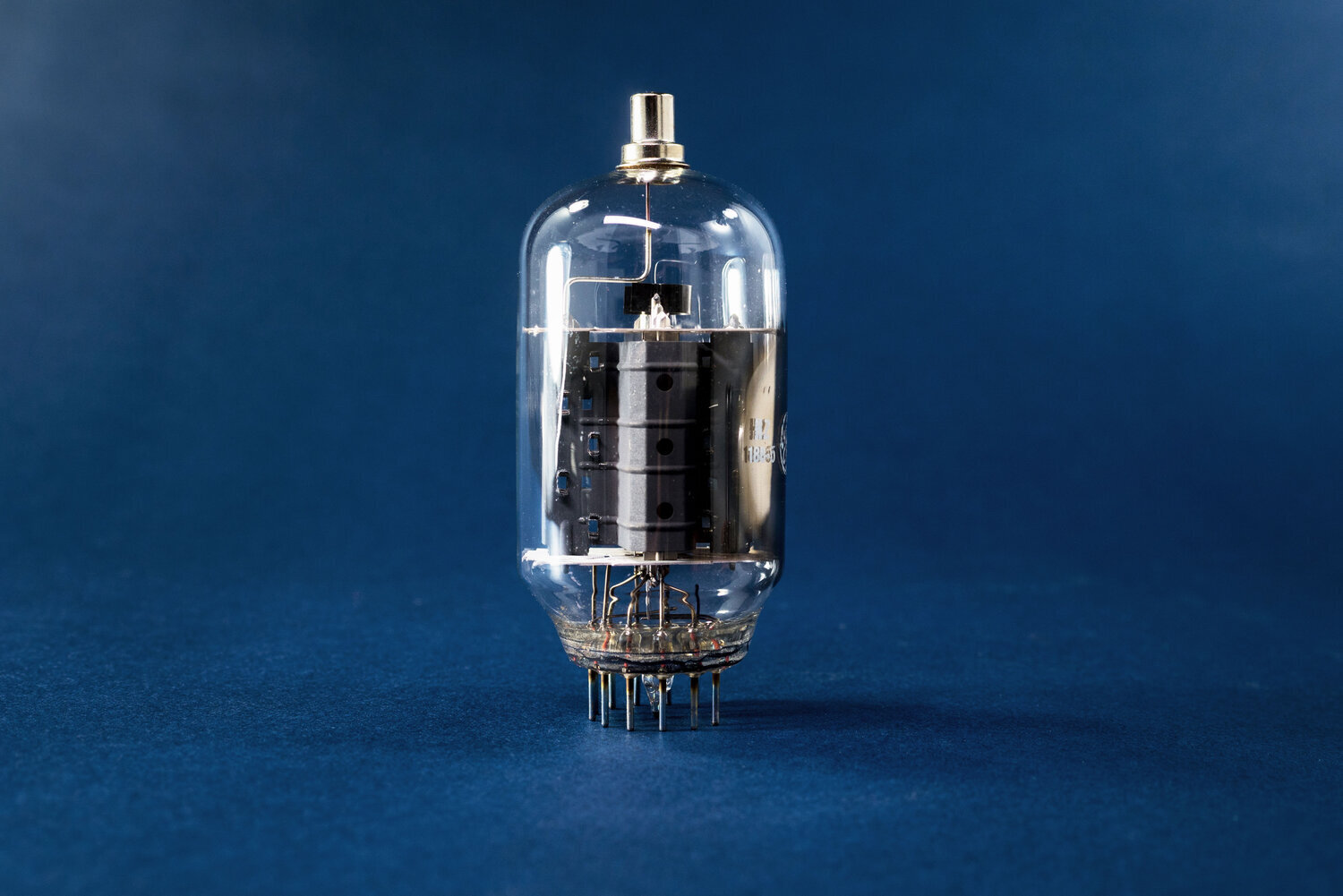

For instance, consider the Danelectro 9100. This is a reverb tank that functions like the ghost of a doomed relative of a 1963 Fender Reverb. The reverb “tank” is a pair of open springs driven by a 6CA4 (that’s a single 7-pin triode) via piezo transducers. The piezo transducers are basically a pair of little crystals wrapped in a piece of fabric that resembles a bandaid, which the spring clips onto. Power supply filtering consists of two 10uf capacitors, period.

The piezo transducers used in the Danelectro are unobtanium. Nobody uses them anymore in any application. So, this is a circuit where an exact 1:1 replacement is impossible. If the transducers are broken, what do you do? Do you replace them with a different kind of piezo transducer? Do you replace them with an Accutronics tank? Then, what do you do with the drivers? Do you replace the original tube-driven driver circuit with a different tube circuit that is better suited to drive the new spring system? Do you replace it with a space-saving solid state circuit?

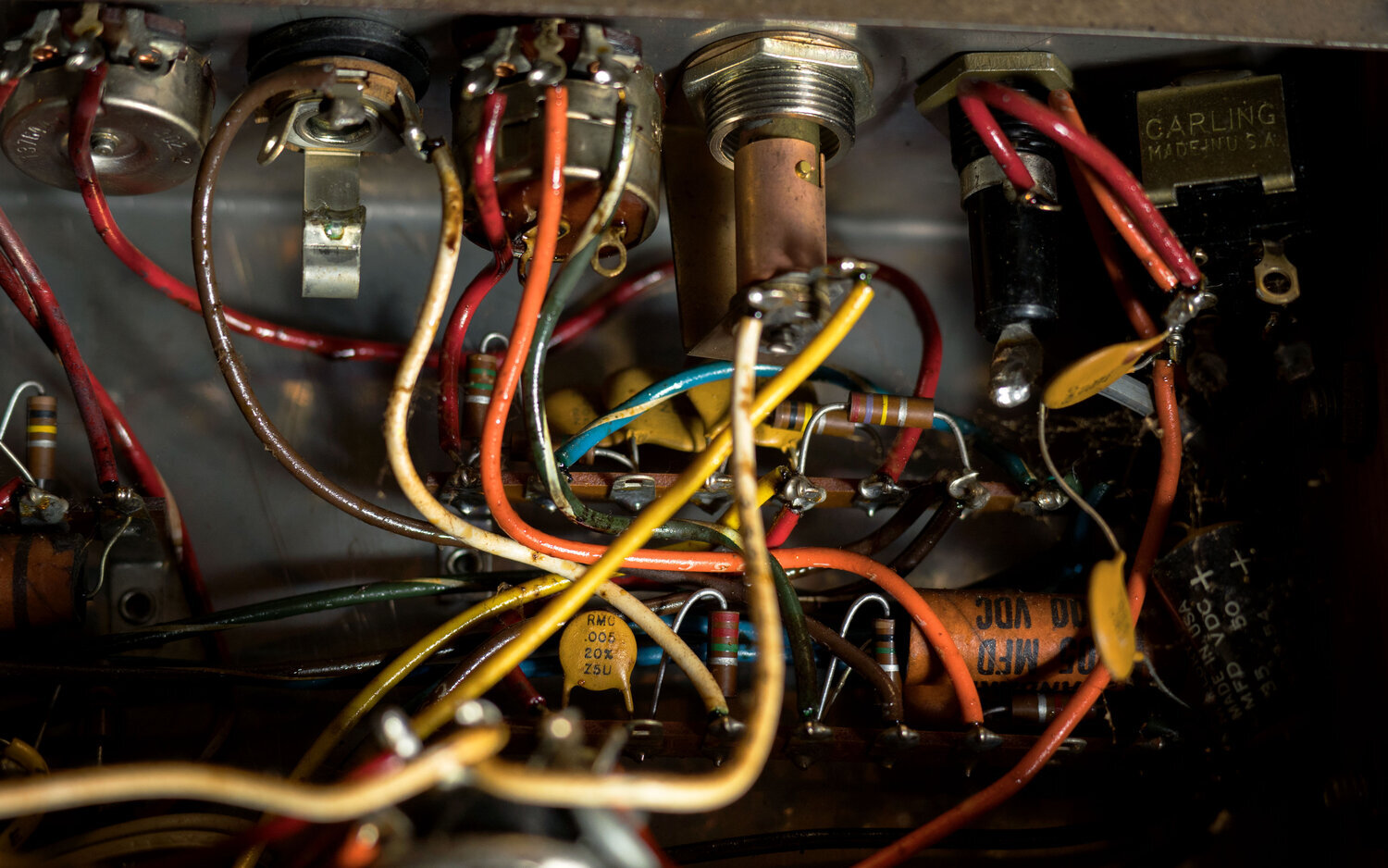

A Wurlitzer 112. We often modify to amplifier to include an fx loop.

Even routine repairs can become mods. When you replace filter caps, do you keep the same values? Should you keep original carbon composition resistors or replace them with low-noise resistors? What about the original ceramic capacitors? From there, it’s a slippery slope to other little changes. What about one more filter stage? Wouldn’t the amp sound better with a couple of grid stoppers? With more (or less) negative feedback?

There is also a point in any amplifier where no further mods are possible. If you want better results, you need a different amp. The chassis is often a major limitation. For instance, in many vintage amps, the transformers are too close together. Good luck moving them! Or, in the Wurlitzer 112, half of the amp is outside of the chassis. There is no way to move that circuitry inside, because it involves jacks that the chassis cannot otherwise accommodate. (The mechanical action of the 112, a rough draft for every Wurlitzer since, is a subject for a whole different article.)

There are simply some things that you have to live with if you want to use a vintage amp. Some amplifiers are just so finicky that you need an open mind to play them. Because they are capable of such interesting and rare sounds, they are worth any inconvenience. But because playing these amps is so much trouble, they probably won’t become your everyday, go-to amp. That’s fine: not every piece of gear has to be a Swiss army knife.

But most issues are in a gray area. What problems should you mod away? What problems should you just work with? How do you get the most vintage mojo with the least inconvenience?

Every will have different answers to these questions. The important thing is that we stop to think before we make any changes to the circuit. Consider:

Why do I have this amplifier in the first place? What do I like about this amp? What are its good features?

What do I not like about this amplifier? Are these things fixable? What changes to the circuit must I make in order to fix these things?

Would any serious musician accept this amplifier in its current condition? Is the amplifier safe and reasonably functional as-is? Am I better off selling the amp and buying a different one that more closely accomplishes my needs?

What do I intend to accomplish with this mod? Is there a less invasive mod that would result in the same outcome?

Is the mod necessary for safety? Is it necessary for quality recording?

Would I use the amplifier more often if I performed this mod?

Is there anything about the amplifier that is historically valuable? Would the mod affect that historically valuable aspect of the amplifier?

Can the mod be reversed in the future?

A late-1950s Wurlitzer 700. For the best recording results, this tube amp requires modification to reduce the noise floor.

Above all, our mods should make the amplifier more functional and more usable. This is our golden rule of modification.

When we repair an amplifier, we try to preserve its vintage character without being excessively sentimental about the components inside. Our goal is to make the amplifier operate to its fullest potential and interface as seamlessly as possible with modern recording gear. Sometimes, it is hard for us to clip out a capacitor that looks really cool. After all, vintage aesthetic is what drew us to these amps in the first place. But, if replacing that capacitor improves the quality and playability of the amp, then it has to go.

It is important to remember that the vintage tone of the amplifier does not rest on any particular point in the circuit. Rather, it is a product of the entire circuit, encompassing everything from its general topography to its chassis and its enclosure, which is itself the product of trends and technology at the time that it was designed. Every facet of the amplifier contributes to its vintage tone. Only truly substantial and irreversible mods could compromise that.

Further Reading

Browse all of our articles on restoring vintage gear. Or, click on an image below.